Mc Kinney, Texas "Best Places To Live in America"

I.

Cognitive dissonance question

When did you first become aware of

race?

Sundown towns are towns like Anna, Illinois, where it is

said that the name ANNA stands for “Aint’ No N-----s Allowed” and where there

is a memory of the town having had signs at the corporate border that say, Nigger, Don’t Let the Sun Go Down on You in

_________________. In Anna, and

nearby Jonesboro, such signs existed as recently as 1970.

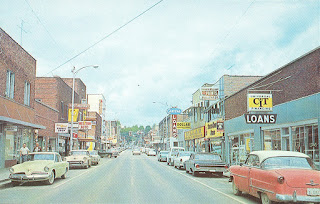

A famous Sundown town in Kentucky is Corbin, the home of

Col. Sanders, who was never really any kind of Colonel, but who was a great

salesman for a fried chicken recipe. Corbin drove out all of the black

residents in 1919 after a poker game between workers on the rail line. Later

the story was changed to one about a rape and a hanging. But from that time on,

blacks were kept out.

Corbin KY, 1930s

Most of these Sundown Towns were started by an incident or

rationalized by a story about a crime, a loss of jobs, or sometimes very absurd

explanations.

In reality the towns were created deliberately, and the

roots were manifold: labor strife (the earliest unions were vehemently racist);

school segregation; the help of the FHA, which made home loans nigh impossible

for African Americans; real estate salespersons and contracts;

Perhaps you, like I, find all of this shameful and a cause

for aversion. You know, though, that it’s true. Places in the South and the

Midwest have been and still are, if not blatantly, then covertly racist.

But, hold on.

In fact, there are almost no Sundown Towns in South.

Almost all Sundown Towns are in the Northeast, the Upper

South, and the Midwest. Some of the most glaring examples are Darien, CT; LaJolla, CA; and the west shore of the Great

lakes near Detroit around and including Grosse Point.

slightly swarthy, or not at all?" and "Accents -

pronounced, medium, slight, not at all?" The

maximum score for the survey was 100, with most

prospective residents needing a score of 50.

However, according to Michigan Attorney General

Paul Adams, "a Pole is expected to have five

additional points. An Italian, Yugoslav, Greek,

Syrian, Lebanese, Armenian, Maltese, Rumanian, or

other southern European is required to have 15

additional points. A Jew is required to have 35

additional points and his points are more difficult

to achieve because of penalties in a special marking

system for Jews. Orientals and Negroes are not

considered at all." (from the SUNDOWN TOWNS website)

pronounced, medium, slight, not at all?" The

maximum score for the survey was 100, with most

prospective residents needing a score of 50.

However, according to Michigan Attorney General

Paul Adams, "a Pole is expected to have five

additional points. An Italian, Yugoslav, Greek,

Syrian, Lebanese, Armenian, Maltese, Rumanian, or

other southern European is required to have 15

additional points. A Jew is required to have 35

additional points and his points are more difficult

to achieve because of penalties in a special marking

system for Jews. Orientals and Negroes are not

considered at all." (from the SUNDOWN TOWNS website)

So.. when we think about the pool party

that was held in Texas, and the out-of-control police officer who sat on a 14

year old girl, we have to place it in a context of white privilege. And while

we are speaking of Sundown Towns, and neighborhoods, we can talk for a moment

about pools.

Perhaps you recall the incident in

2009, when a group of children from a Daycare in Huntington Valley, PA, were taken to a private swim club and then, the following day, asked not to return?

It happens that the children were all African American and Latino. “We don’t

want to change the atmosphere and the complexion of the club,” the manager

said.

The daycare sued. The 60 kids and the

daycare were awarded over 1 million dollars.

One little boy was interviewed, a guy

about six. You know what he said? He said that when they got into the pool, the

white parents started getting their kids out of the pool. He heard them saying

things about the black kids.

This is painful. This makes us feel

uncomfortable. We don’t want to know these things.

Valley Club pool

But that is the swim club, the pool,

that my Uncle Don and Aunt Julia took us to whenever we visited them in the

summer. I recognized it right away when I heard the stories. Going there was

such a treat. They had pretzel sticks and I used to get one and put mustard on

it. I can recall so many details of the days we spent there, carefree and

joyful. But, of course, I didn’t know, nor did anyone tell me, that what I

enjoyed was denied, and would still be denied 50 years later, to kids of color.

I think the pool/swimming issue is particularly painful and present, is one we can all touch upon. For there is almost no one who did not go swimming someplace during the summer, and who did not realize, at some level, that a form of racism was being exercised in who could and could not swim where. By the way, The Valley Swim Club finally declared bankruptcy and is now closed. And the children, their counselors, and various community groups are receiving their portions of the settlement. But what sum of money can erase the memory of being SIX years old and having white mothers pull their children out of the pool when you jump in? In 2009? In Pennsylvania. Not Kentucky, not Alabama. the suburbs of Philadelphia.

When we think about pools, about swim

clubs, and exclusion, we are talking about suburbs. And in his book and

website, Sundown Towns, Prof. James Loewen proves convincingly that

virtually every suburb that was intentionally formed was created as a

sundown town.

The real issue is: Why did we never ask

a question? A simple question, such as, “Why do so many Black people live in

Camden?” or “Don’t African American people want to go to the shore?’ and if we

asked, and the answer made no sense, why didn’t we make it our business, once

we were old enough, to say something, do something, make waves, make at least

some ripples?

Actually, the house I live in is very likely to have been on the Underground Railroad, as the town of Haines'Port, like all of the surrounding towns, was founded by Quakers, all of whom were very active in the Underground RR. Lately, I have been looking at some of the nooks and crannies in the basement and attic and wondering which ones were devised to hide escaping slaves. I wish they could tell.

My childhood home, Hainesport N.J.

Sadly, these Quakers were no so peaceful when it came to the Lenni-Lenape Indians, whom they displaced from the entire area. But, at least, the truth about that is told. It would be rather difficult to lie.

Mt. Laurel Friends Meeting House

My father referred to a road near us as “Jewtown.” I had no idea what that meant, nor did I meet anyone who was Jewish until much later in life. But on that road, in addition to some very dilapidated and decrepit buildings and houses, was one that intrigued me. On it was a symbol that I now realize as the Star of David. In the 1960s, almost all of the Jews of Mt. Laurel had left that intentional ghetto and had sold their homes to poor whites and African Americans.

But the story is way more complicated.

“Jewtown,” also known as Springville, had been populated by freed Blacks and tenant farmers since the 17th century. This is understandable, since

we know that Mt. Laurel, like many of the surrounding towns, was founded by

Quakers, who not only employed and lived peacefully with freed Blacks, but

actually operated the Underground Railroad. Only after WWII, when Blacks sought

an end to segregated schools, and proposed to build housing for low income

families, did the Sundown policies begin. In 1970, the Mayor spoke to citizens

at the AME Chapel and told them: If you

can’t afford to live in our town, then you will just have to leave.”

Jacobs Chapel AME Church

(ironically, if you go to the Mt. Laurel webpage, the only photo under historic places is this chapel. Yet no mention is made of the landmark case that changed the face of public housing, albeit by fits and starts)

All of this, and lawsuits that

followed, gave rise to the Mt. Laurel I and II decisions, NJ State Supreme

Court Decisions, as well as the 1985 Fair Housing Act, all of which provide for

an allotted number of low and moderate income housing units in every

municipality. Still, many zip codes get around this, as they are able to “buy”

off part of their obligations by supporting housing projects in neighboring

cities or towns. But these are landmark cases, as important to race relations

as Brown v. Board of Education. I am appalled that I knew nothing, and that no

one told me, and that later, I didn’t pay attention.

Gradually, I learned some of these things. But not until long

after I left this state. I lived there. I rode my bike past the former synagogue.

I benefitted from the privilege of living in Hainesport, Moorestown (which once

only allowed Blacks in the back row of its movie theatre), and at the Jersey

shore, where African Americans (and Jews) were excluded both actively and

passively, and in some cases still are. Did you know that there were gates at

the entrance to Ocean Grove that separated it from Asbury Park? They are no

longer there, but longtime residents are sure that the purpose of these gates

were to keep A-A out after sundown. Of course, Ocean Grove is a wonderful

Christian place, so maybe that isn’t true.

Finally, I wonder whether anyone who lives in Mays Landing or

Hamilton township has heard of Mizpah? This part of your township was formed as

a Jewish community for a group of cloak makers although it died out as a

community. I wonder who lives there now? Are they white or African American?I

am asking this because Hamilton Township is listed in Dr. Loewen’s database

along with this report:

Mizpah Cloak Factory and the Jewish community

Mizpah Hotel (1930s)

Mizpah, NJ... an African American community

about 15 miles west of Atlantic City. A former mayor

recalled growing up in the town, and how there were

no blacks allowed after dark in the Mays Landing

village section of the township, with the exception of

the town barber. Instead, everyone of color was

required to live (and to this day many still do) live

about five miles west in the Mizpah section of the

township. They were informal restrictions, he said, but

they existed.

Here is

another report from a Cape May County area resident:

I grew up in Southern

New Jersey, on the Delaware bay. And I have never lived in a more overtly

vicious racist area, and I have lived in both NC and VA the last 23 years. My

aunt lives in Dividing Creek, NJ, a very small redneck village close to Newport

and Fortescue. It has never allowed a black family to live there. Ever. Just a

few years ago a very brave family did, and their HOUSE was burned down while

they were away. Homes proudly fly the Battle Flag.

As Loewen shrewdly notes, “our

culture teaches us to locate overt racism long ago (in the nineteenth century)

or far away (in the South) or to marginalize it as the work of a few crazed

deviants.”

(Dan Carter)

As I read Loewen’s book, however, it seemed to me that white

Northerners chose a different path: amnesia.

It is, I suppose, the natural response of most cultures

when confronted with a painful past. “Every nation,” wrote the

nineteenth-century French philosopher Ernest Renan, “is a community both of

shared memory and of shared forgetting,” what British statesman William

Gladstone called “a blessed act of oblivion” that allows old adversaries to put

aside past grievances and live together in peace.

But we are not living together in peace. We are living separately, in suspicion and

distrust. Everywhere we look, we see the long shadow of our racist past in the

re-segregation of our public schools and the growing isolation of the poorest

African Americans in impoverished inner cities, in the continuing wealth and income

gap between black and white, and in the unconscionable explosion of a

“prison-industrial complex” that incarcerates millions of black men, consigning

them to a lifetime in the shadows of our society.

None of us should feel personal responsibility for what

our parents or grandparents did or did not do. But there will be guilt enough

for our own generation if we do not confront and address the bitter

consequences of the story that James Loewen has revealed so powerfully in Sundown

Towns.

II.

Allies

When we learn about these things, what then can we do?

According to Loewen, there is a great deal that can be done, and should be done. Indeed, churches and civic organizations are just the groups to do it, because clearly, neither chambers of commerce, Historical Societies, or locals who benefit from and/or are uncomfortable with white privilege have done anything nor will they.

We can do the research. We can work for legal solutions, reparations, recognition, or reconciliation.

We can help to be agents of truth telling to present and future generations.

We can apologize for our inability to see what we should have seen so clearly, for being a part of the problem and accepting the benefits that came along with it.

III.

Opportunity

In

w hat ways is the sky opening up now?

Residential segregation is one reason race continues to be such a problem

in America. But race really isn’t the problem. Exclusion is the problem. As soon as we

realize that the problem is white supremacy, rather than black existence or

black inferiority, then it becomes clear that sundown towns are r racial

inequality is encoded in the most basic single fact in our society—where you

can live—the united states will face continuing racial tension, if not overt

conflict. (Loewen, p. 17)